[Guardian

Unlimited, U.K.]

Jornal de Negocios, Portugal

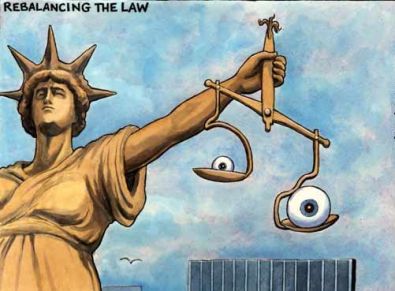

Unlike Portugal, America Knows How to Punish the Guilty

"In the United States, financial

crimes are punished with disturbing violence. Ö we [in Portugal] donít know how

to punish. We donít know how to do it in the courts, in schools or in companies.

Our incapacity to effectively punish has significant social costs - it makes us

unjust toward both the innocent and the guilty."

By Jorge Brito Pereira

†††††††††††††††††††††††††† ††††††††††††

Translated By Brandi Miller

February 6, 2009

Portugal

- Jornal de Negocios - Original Article (Portuguese)

In the United States, financial

crimes are punished with jarring violence. Looking at just a few of the cases

which in recent years have recieved most media attention, Bernard Ebbers [video in photo box], the

former CEO of WorldCom, was sentenced to 25 years in prison; Andrew Fastow, the

former CFO of Enron, was sentenced to ten years in prison (later reduced to six),

and with him 14 other high-ranking officials from the company were sentenced;

L. Dennis Kozlowski and Mark H. Swartz, former CEO and CFO of Tyco

respectively, were sentenced to eight to 25 years in prison; John Rigas, founder

of Adelphia Communications and his son Thimoty were sentenced to 17 and 12

years in prison respectively; the popular TV host Martha Stewart was sentenced

to five months in prison (and three months house arrest) for having lied about her

motives for selling of 3928 shares of ImClone Systems, a company run by a

friend, Sam Waksal, shortly before just a bit of bad news caused the stock

price to fall. The list is endless.

But much more disturbing than

the violence of these sentences, is to see the difficulty we have in Portugal criminally

punishing those behind financial crimes, and more generally, scandals covered by the press. The

phenomenon, which is more noticeable in regard to financial crimes - is a topic

that perhaps still exist for reasons of public censorship (or a lack thereof). This

helps explain why these misdeeds are relativized along with many other types of

crimes, with the reasonable exception of blood crimes.

Every time news appears

in the press about possible criminal action involving a public figure, the

first reaction is invariably a popular lynching. Typically, there is a deafening

social roar that clamors for the application of exemplary, disproportionate and

inappropriate punishment. Since justice is slow and indelicate in its application,

this first stage can last for months or years, and only cools when the targets,

after seeing - often belatedly - that the great fire has burned out, remove

themselves from the public square. Only a few realize this in time - and

thus escape only slightly singed.

The second stage - certainly

the most dramatic - is the legal process. While the fire fed by media accusation is

genuinely hellish, with the verdict, we also invariably see the fire die down. When

there is little left but ashes, the process becomes a bureaucratic nightmare in

which the rules designed to protect the accused are used and abused by the defendant;

years and thousands of pages of proceedings later, even a model case is transformed

into a process with divided results, and where the public no longer knows where

fault lies.†

Posted by WORLDMEETS.US

The truth is that we [in Portugal]

donít know how to punish. We donít know how to do it in the courts, in schools

or in companies. This is in our soul and our blood; it is part of our culture

and our being; we are inquisitors and promoters of redemption; we are strong

with the weak and weak with the strong; we have encompassed within ourselves both

strong and weak - and so we lose the equilibrium required to govern the

application of justice. The critique of violence of guilt that feeds the initial media

fire has the same intensity as our capacity for redemption - the mediation of human

beings characterized by our Catholic upbringing - which rsults in the form of a muddled

final pardon.

Our incapacity to

effectively punish has significant social costs - it makes us unjust toward both

the innocent and the guilty; it allows a social judgment to impose itself on

the legal process; it creates a weaker and less secure society, particularly when

compared with those that deal more justly with both guilt and punishment.

CLICK HERE FOR

PORTUGUESE VERSION

[Posted by WORLDMEETS.US

February 13, 1:47pm]